My mother died. A computer tried to console me.

Facebook's AI program read the comments for me. I'm not sure it made me feel better.

My mother died on Aug. 25, at home in her bed in North Carolina, my stepfather holding one of her hands, me holding the other. It was something we both expected — had in a way welcomed after all that she (we) had been through.

Every living thing dies. Every human mourns. I’m still “processing” my mother’s death, as they say. Something else is processing it1 — and quite literally, too: the computer.

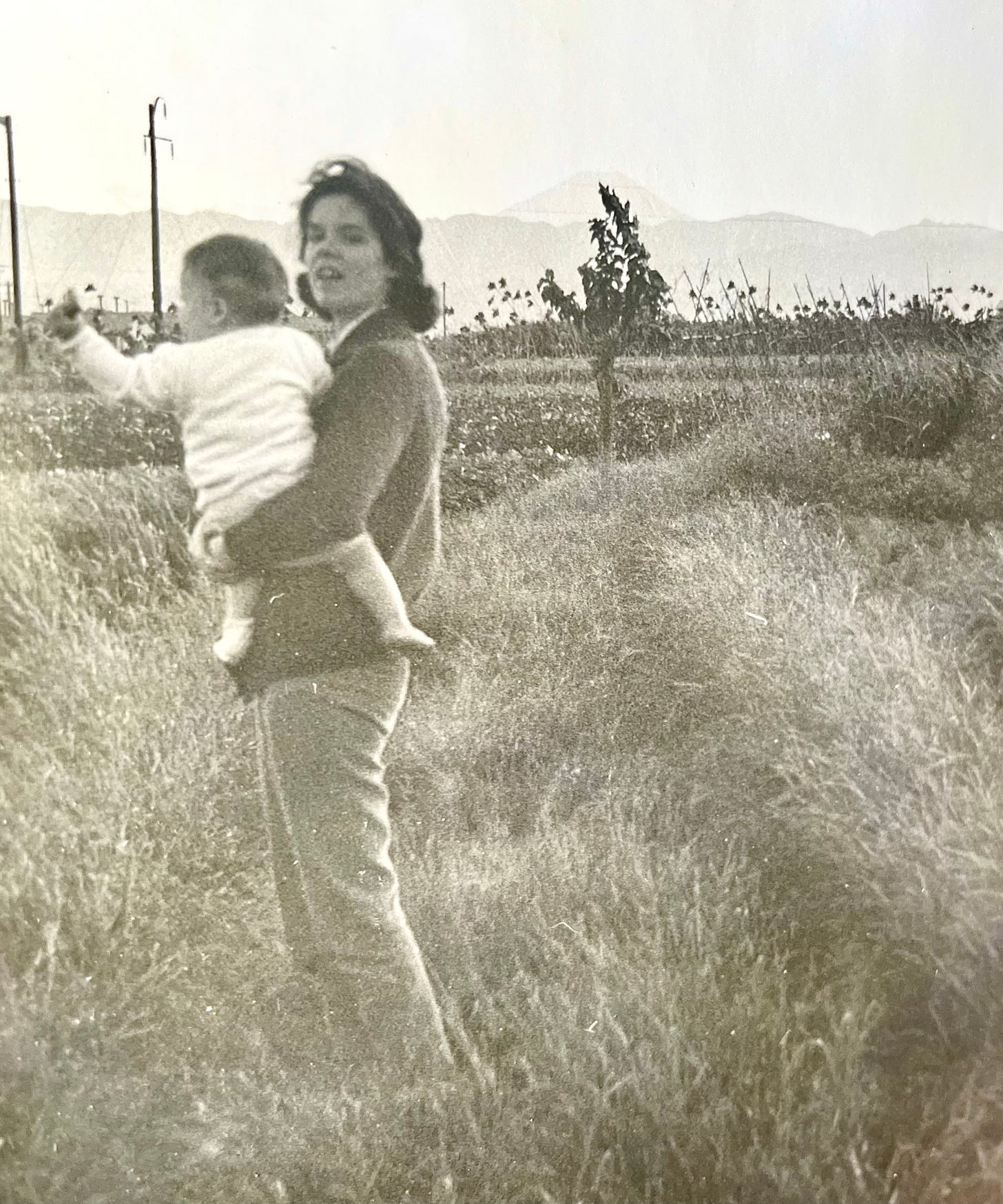

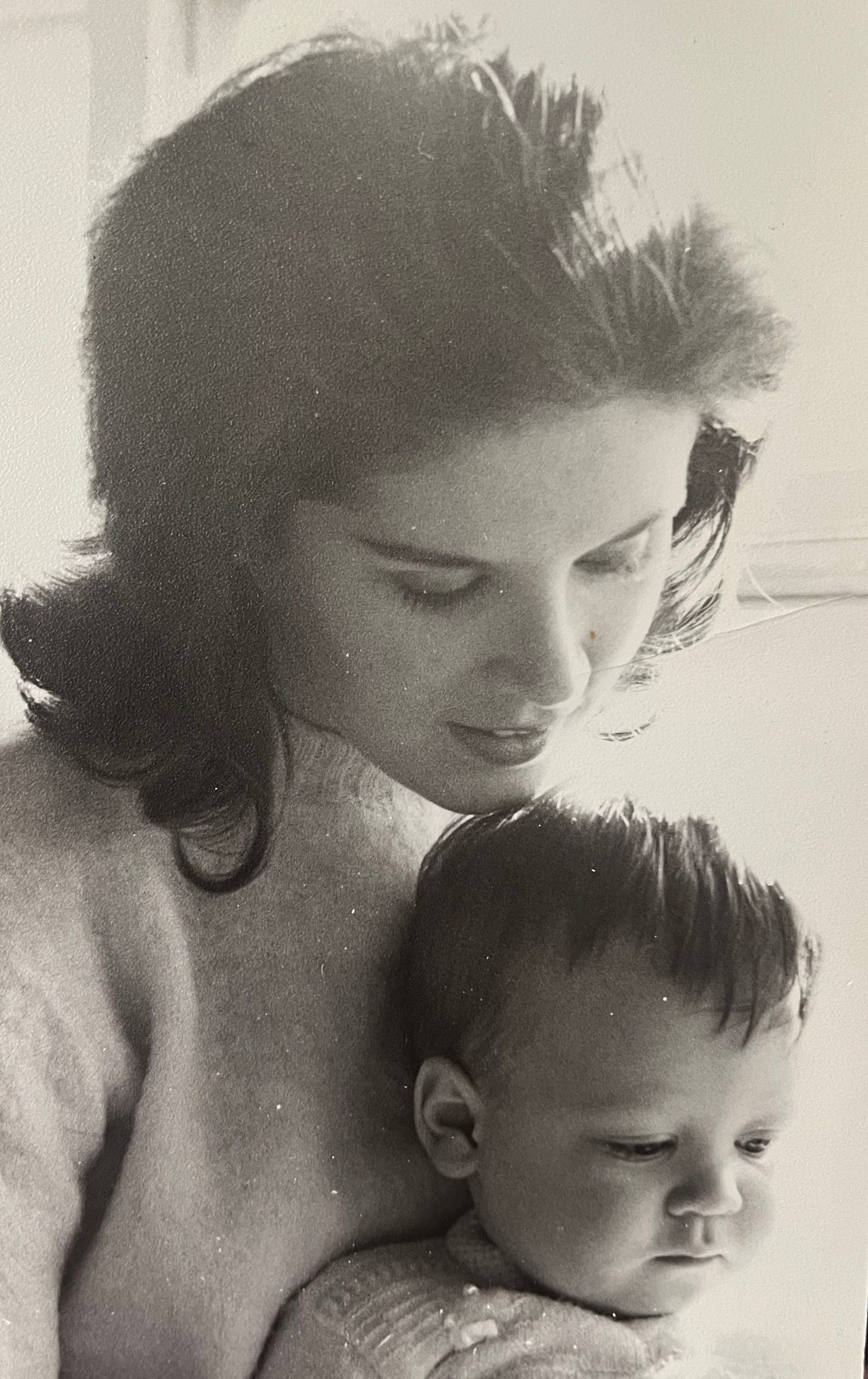

A few days after the death of Margaret Ann Kelly (Sept. 9, 1940-Aug. 25, 2024), I posted a photo of the two of us on Facebook. She’s younger in that photo than my youngest daughter is now. She’s holding a 10-month-old me. I was consoled by the hundreds of comments that friends posted on Facebook. Soon, something else was commenting.

Meta AI added a note to the top of the comments, headlined “What people are saying.” The AI tool had apparently combed through the comments, crunched them, then created a concise precis:

Commenters offer heartfelt condolences to John for the loss of his mother, Peggy Kelly. They express gratitude that he was able to be with her during her final moments and cherish the memories they share. One commenter notes that a mother’s hug is eternal, highlighting the lasting impact of Peggy’s love.

Every day, the AI would update the summary, refining it after reading newer comments:

Commenters offer heartfelt condolences to John for the loss of his mother, Peggy Kelly. They share moving sentiments, acknowledging the significance of his presence at her passing and cherishing memories. One comment poignantly notes, “A mother’s hug is eternal.”

And again:

Commenters offer heartfelt condolences to John for the loss of his mother, Peggy Kelly. They share moving sentiments about the eternal nature of a mother’s love and the comfort of cherished memories. One commenter poignantly notes that John’s mother will always be with him, even though he outgrew her arms.

A week later, I posted a link to the death notice I wrote that was printed in The Washington Post. Meta AI parsed those Facebook comments, too:

Commenters praised the heartfelt tribute to Peggy Kelly, sharing condolences and admiration for her vibrant spirit.

It was weird, this computer “thinking” about my mother’s life and death. There was nothing wrong with what it wrote. In fact, the sentences were pretty accurate, right down to the punctuation. But the words it used — love, cherished, heartfelt, eternal, spirit — were words no computer could ever comprehend.

The AI was all surface, all flat affect. It was numbers, not poetry. A summary like this might have more accurately reflected what I was feeling and feel still:

Sadness. Anguish. Grief. Commenters wish they could make John feel better. They know that death is forever, that life is a mystery. Why do we live? Why must we die?

Later, I pulled together old family photos for a slide show for a memorial gathering we had for Peggy. As I dragged each photograph into PowerPoint, the computer offered a helpful text description stripped across the bottom of the image. Again, there was nothing wrong with these descriptions, except that they were hardly adequate for the emotions I felt looking at them:

A person with long black hair

A person holding a baby

A person and two boys sitting on a bench

A person and person sitting at a table with wine glasses

A person in a kayak

A person. Her hair was long — long and black and lustrous. The baby was me. The boys on the bench were me and my brother, Chris. The “person and person” were my mother and her husband, Bob; they both loved wine. The person in the kayak was my mother.

And yet, those simple descriptions reminded me of what a mother says as she flips the pages of a a picture book, her toddler on her lap. This is a baby. This is a person holding a baby. This is a bunny2, a dragon, a witch, a waterfall, a rainbow. This is the world.

That’s what my mother gave me: the world. The real one, not a simulation.

It explains why after jumping into Substack, I’ve slacked off. I hope to be back.

Pat it. Pat the bunny.

You could always tug a tear out me, John Kelly. A wonderful, human musing.

Good call, John, do what you have to do. My own mother is still with us at age 94 - though perhaps that's not really true as I reflect upon my last conversation with her by telephone months ago. Sometimes I think she transitioned from Mother to Friend while I was in High School and then University and she was busy with her third husband and the sometimes poorly fitting fragments of three families. She had long said that she and I grew up together after I was born when she was just short of 20 years old having married just over a year earlier. He most recent decades have been spent in her own home behind my brother's house in Florida with grandchildren and great-grandchildren among her regular visitors.